"A Change is Gonna Come"

The decade of 1963-1973 represents a critical transition in the civil rights movement for African Americans supporting Black Liberation and Black Power initiatives. Led by LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka), African American artists, including Romare Bearden, Benny Andrews, Vivian Brown, Mari Evans, Sonia Sanchez, and Larry Neal, successfully linked art and politics in an effort to raise black consciousness and change the vision of what liberation for black people looked like.

In effect, the Black Arts Movement (BAM) asserted and advanced a global vision of new political directions and possibilities for black people to embrace, which were connected through the sociocultural aspects of the arts, their production, and reception. Radical in terms of its non-conformist approach to negotiating the challenges related to the politics of integrating a white dominated society, BAM artists were able to see America for what it was: a nation bent on denying people of African descent their humanity.

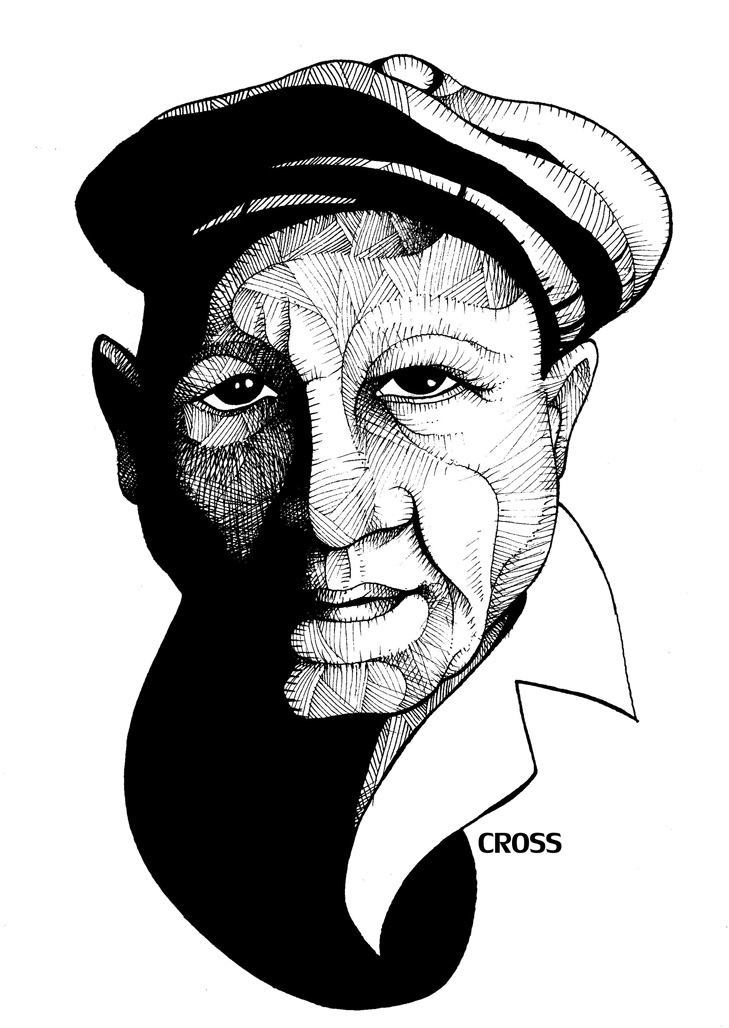

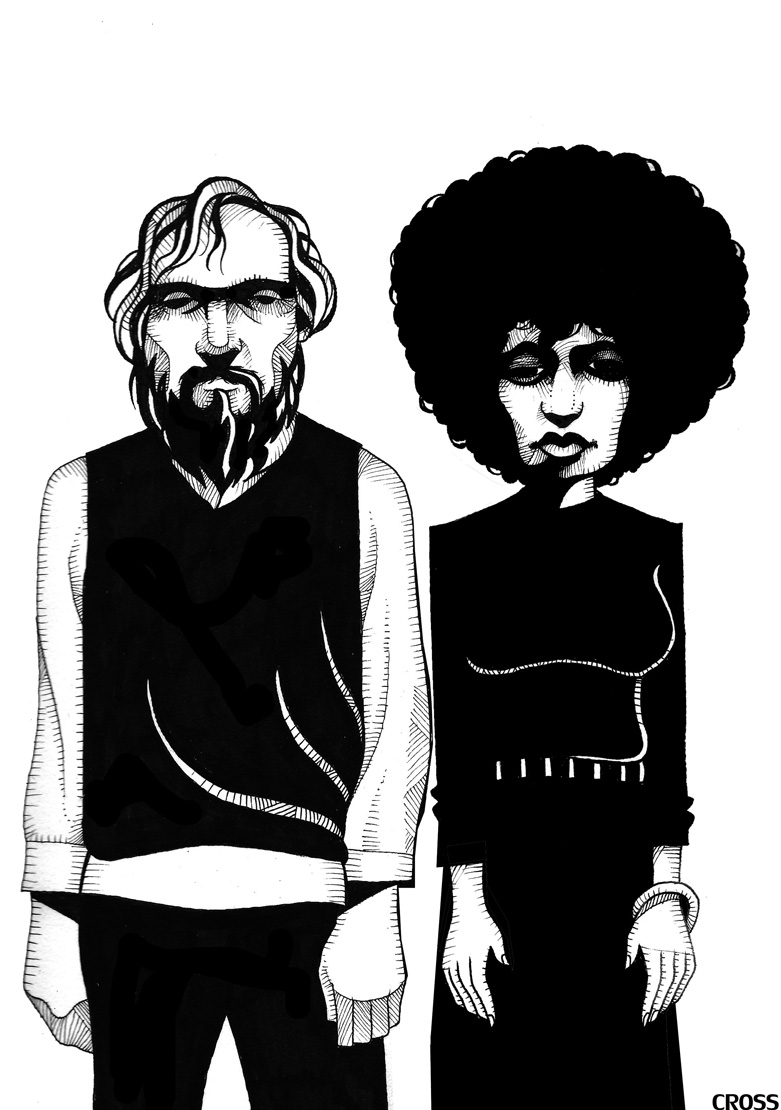

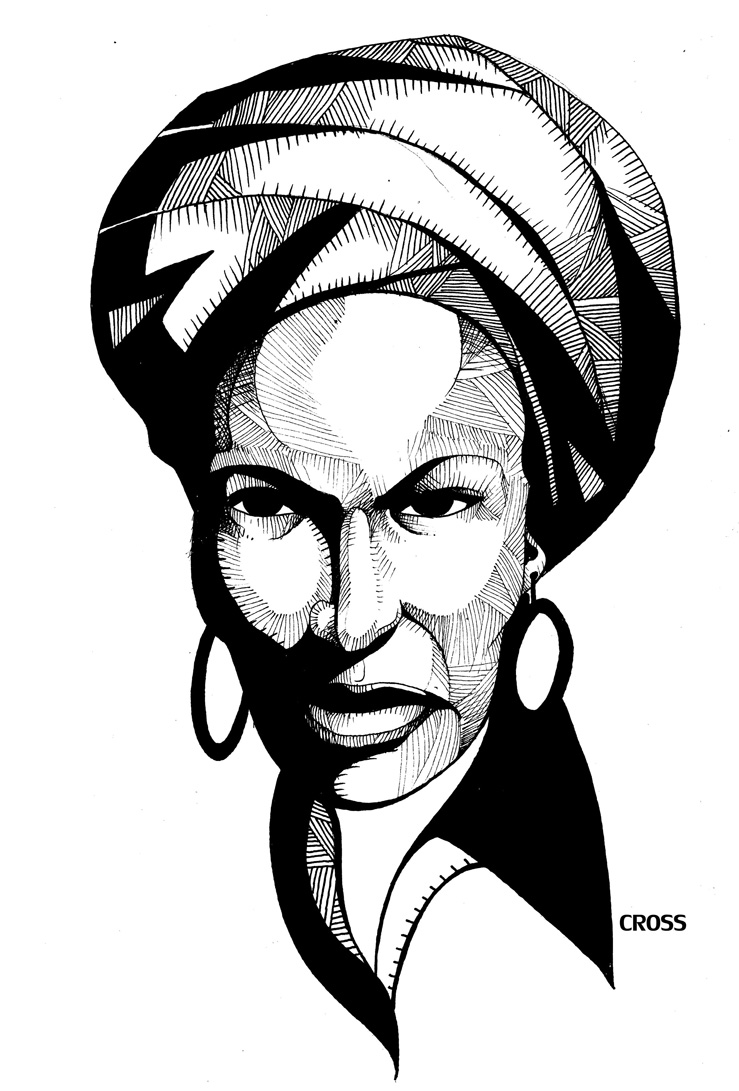

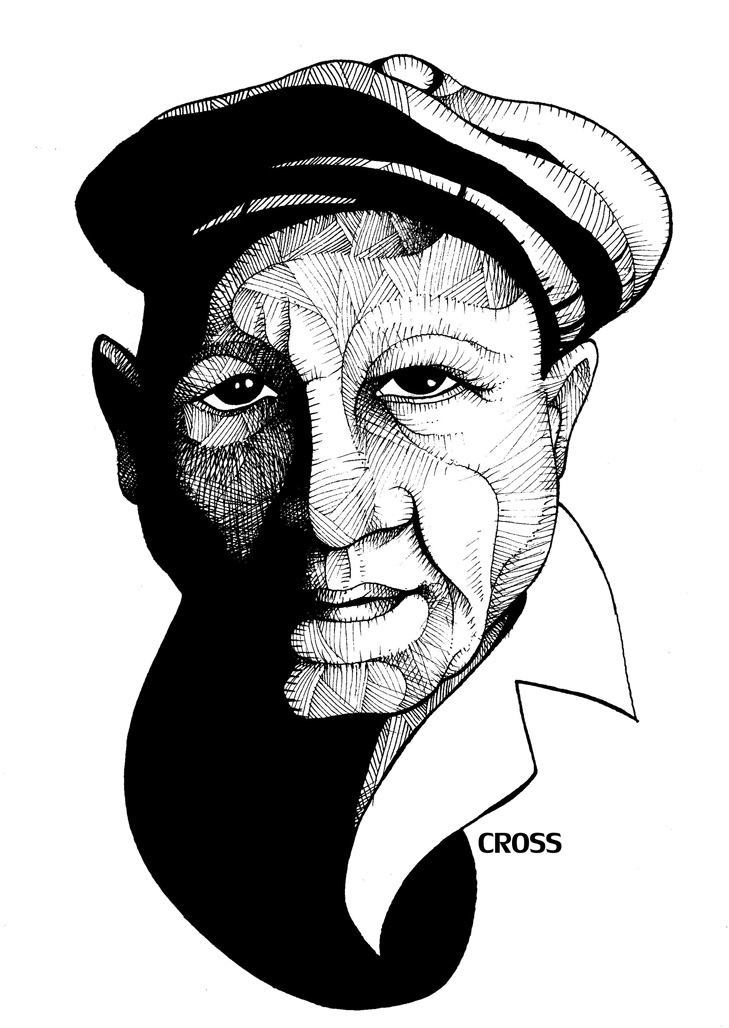

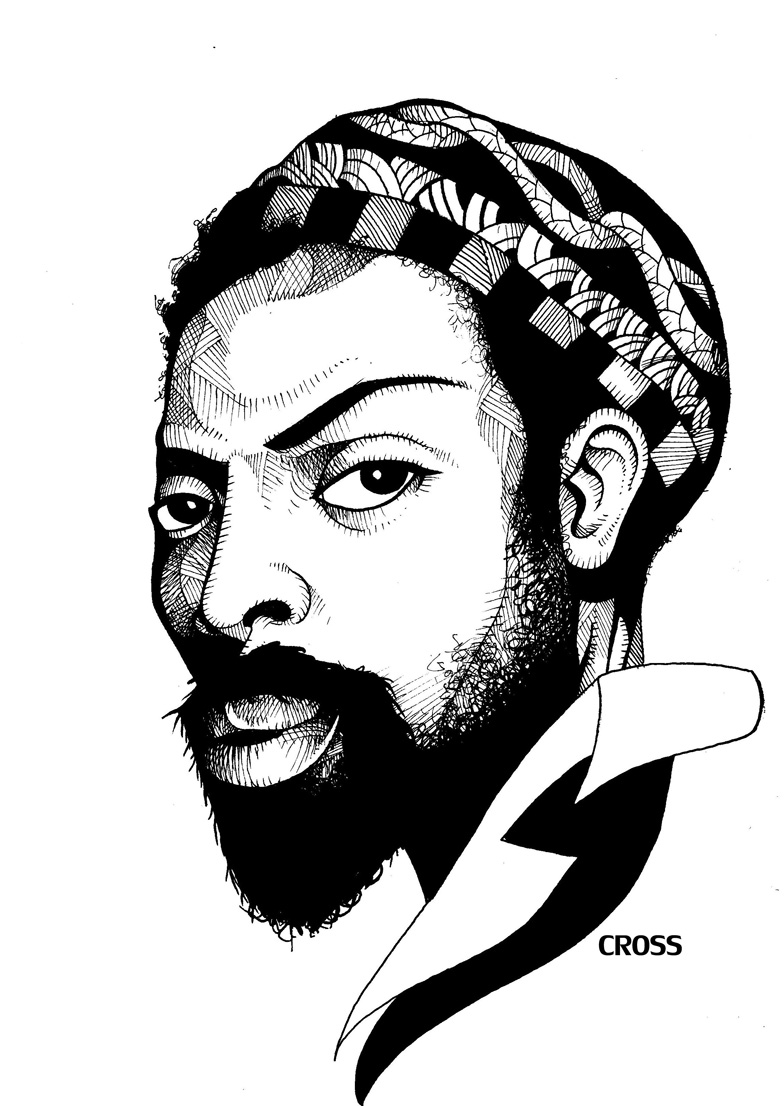

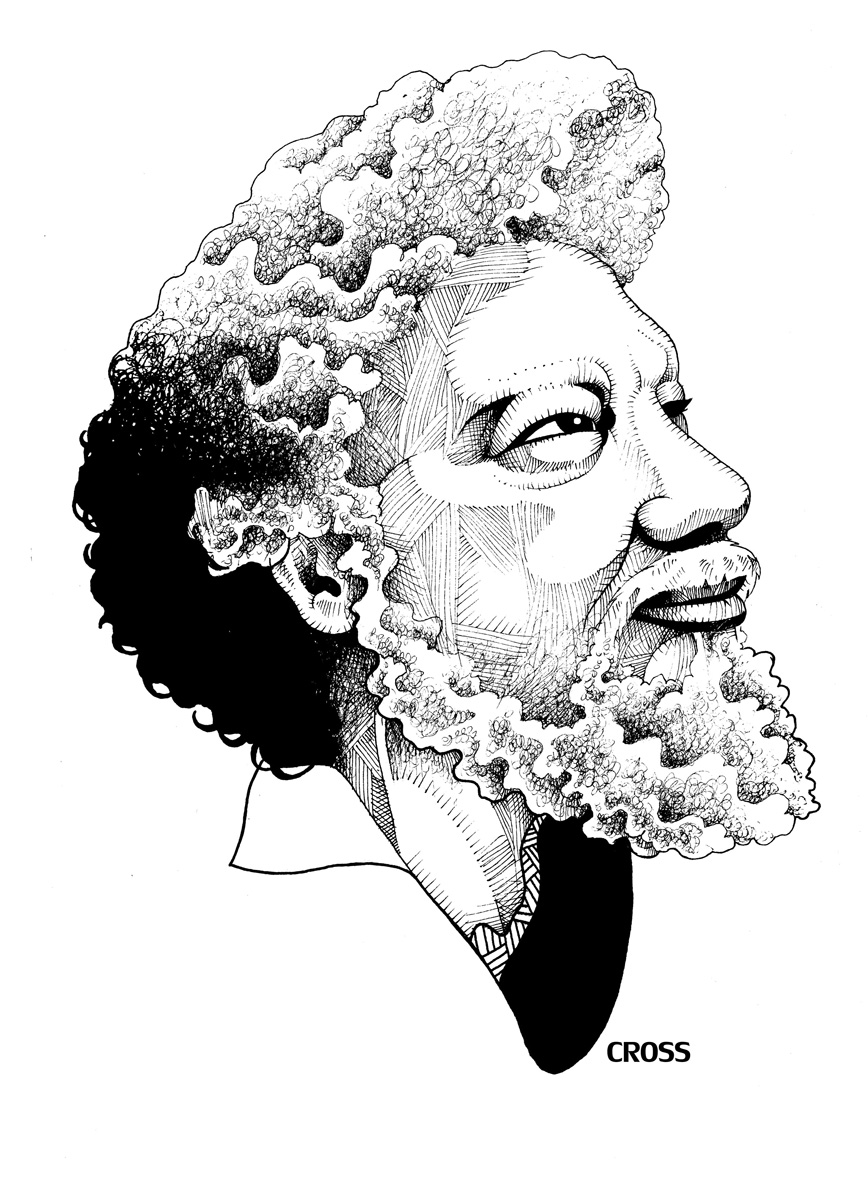

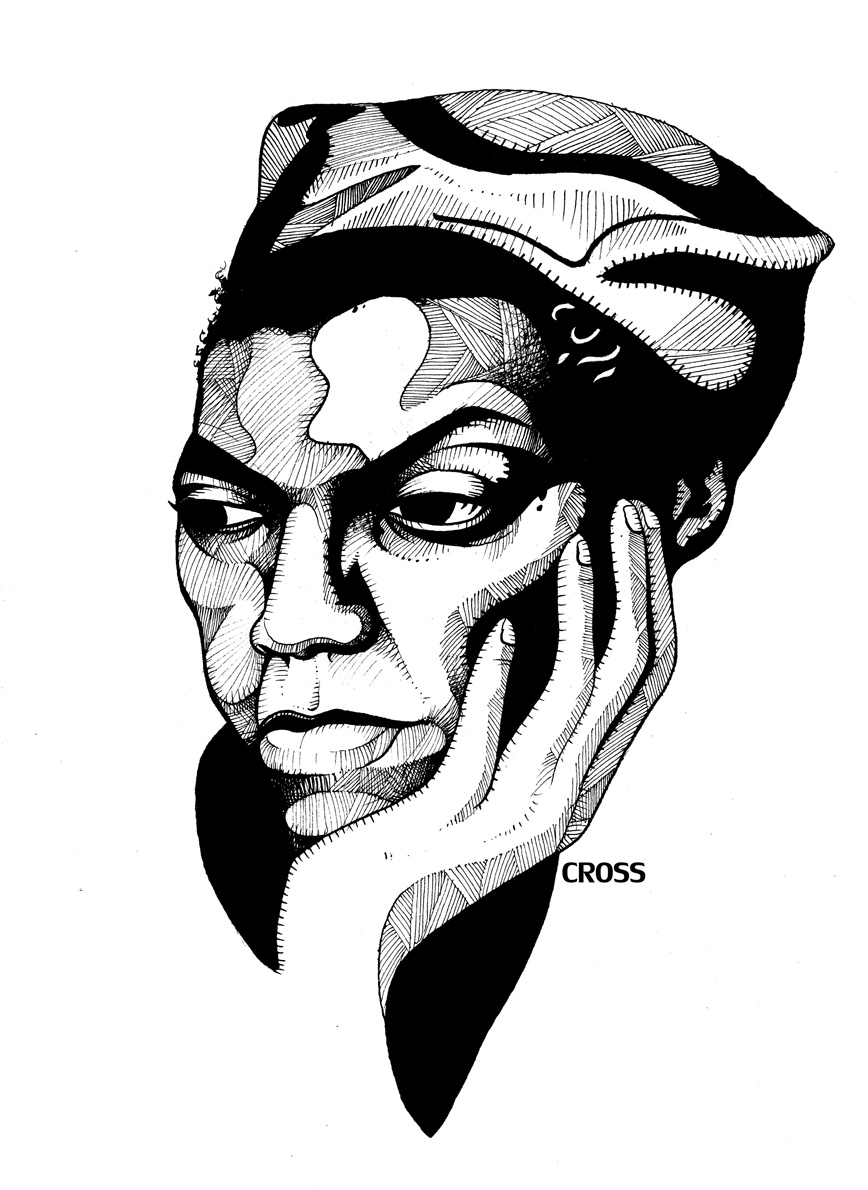

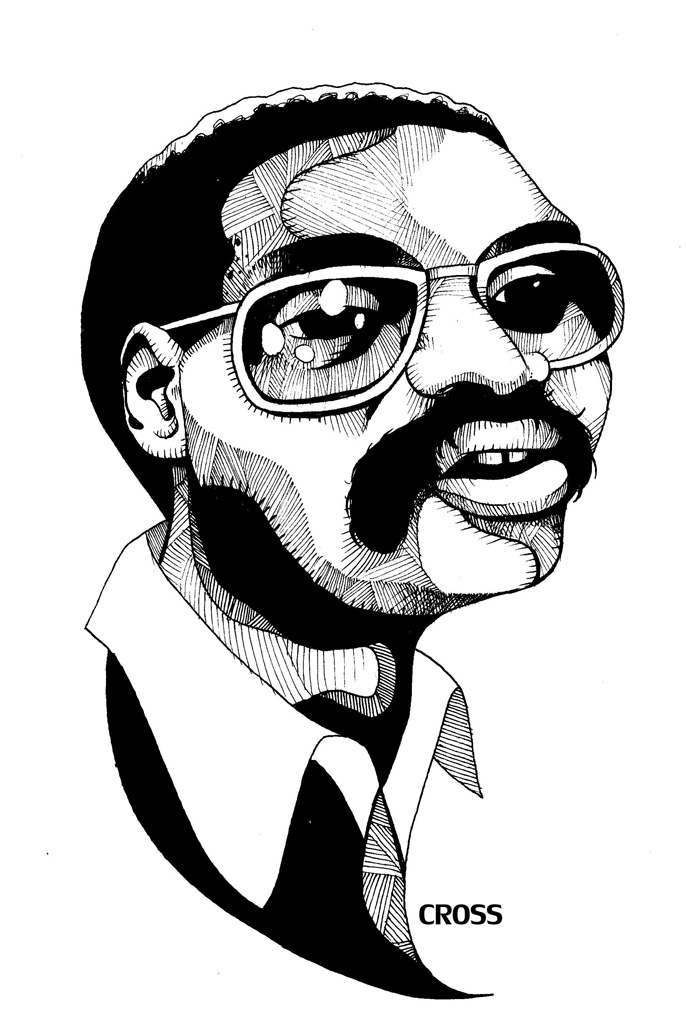

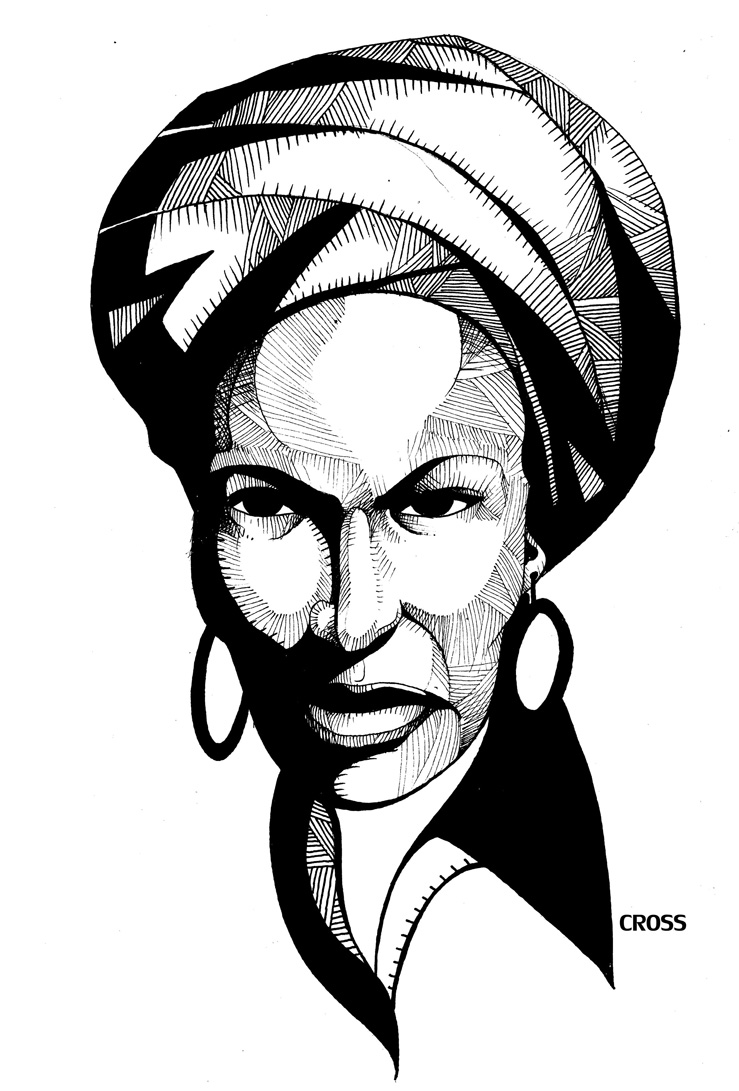

Image: Portrait of James V. Hatch and Camille Billops by artist Keef Crossley, 2015 (All portraits here are by Crossley and housed in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.)

-

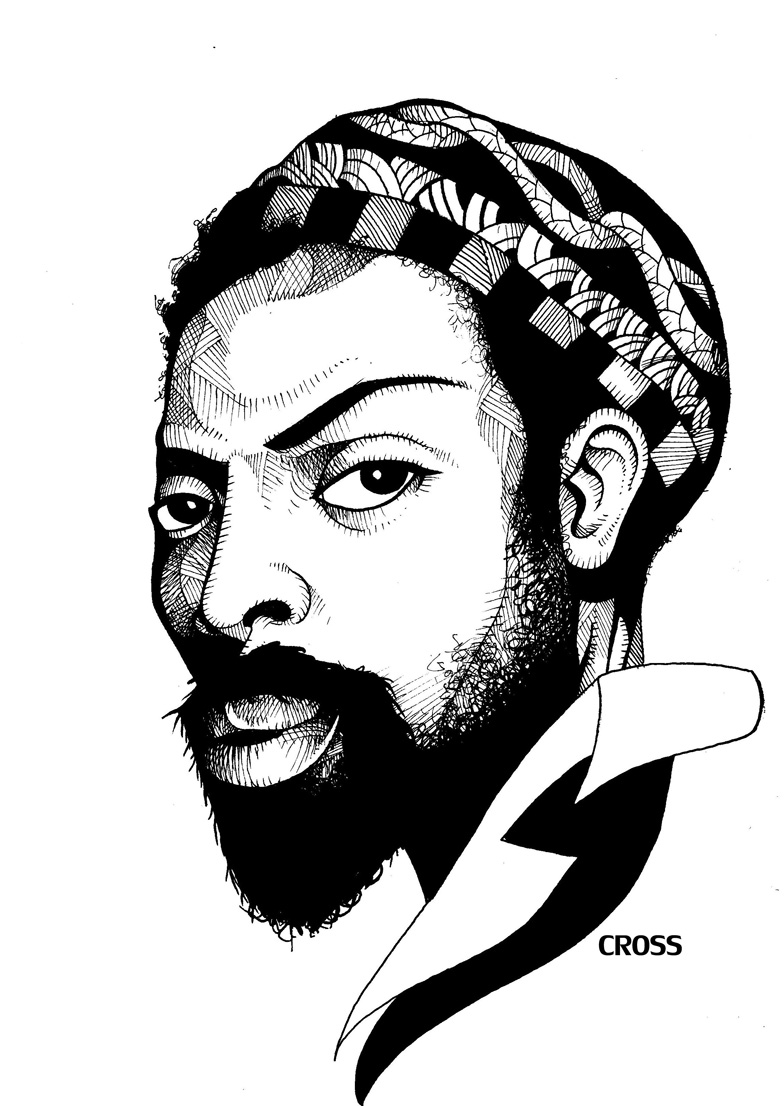

Amiri Baraka (1934-2014)

Amiri Baraka (1934-2014) -

Benny Andrews (1930-2006)

Benny Andrews (1930-2006) -

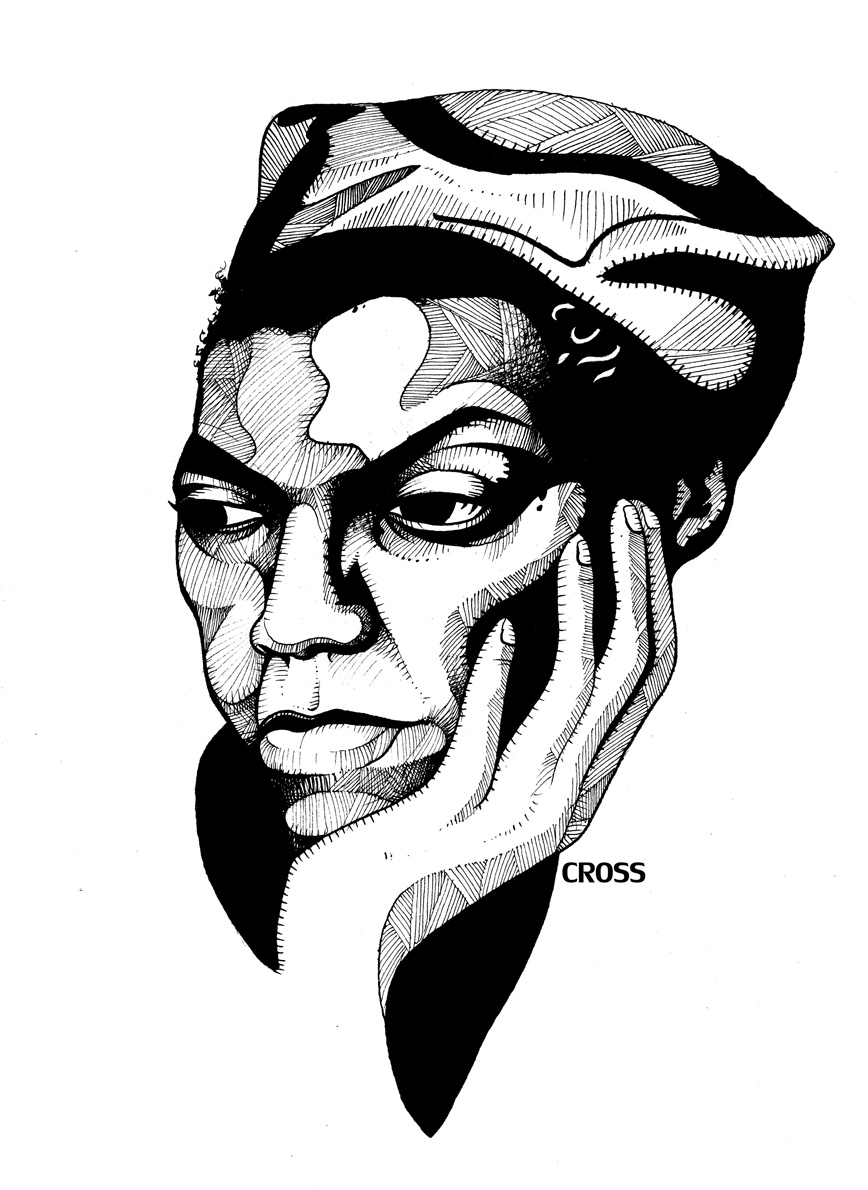

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000)

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) -

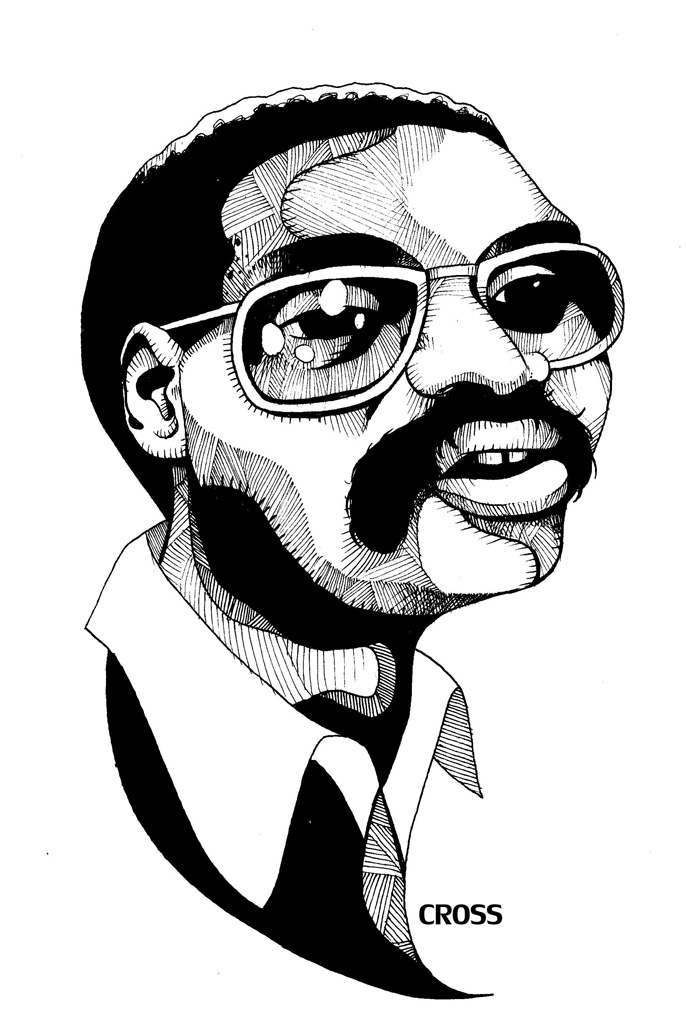

James Baldwin (1924-1987)

James Baldwin (1924-1987) -

Sonia Sanchez (1934- )

Sonia Sanchez (1934- ) -

Larry Neal (1937-1981)

Larry Neal (1937-1981) -

Mari Evans (1923-2017)

Mari Evans (1923-2017) -

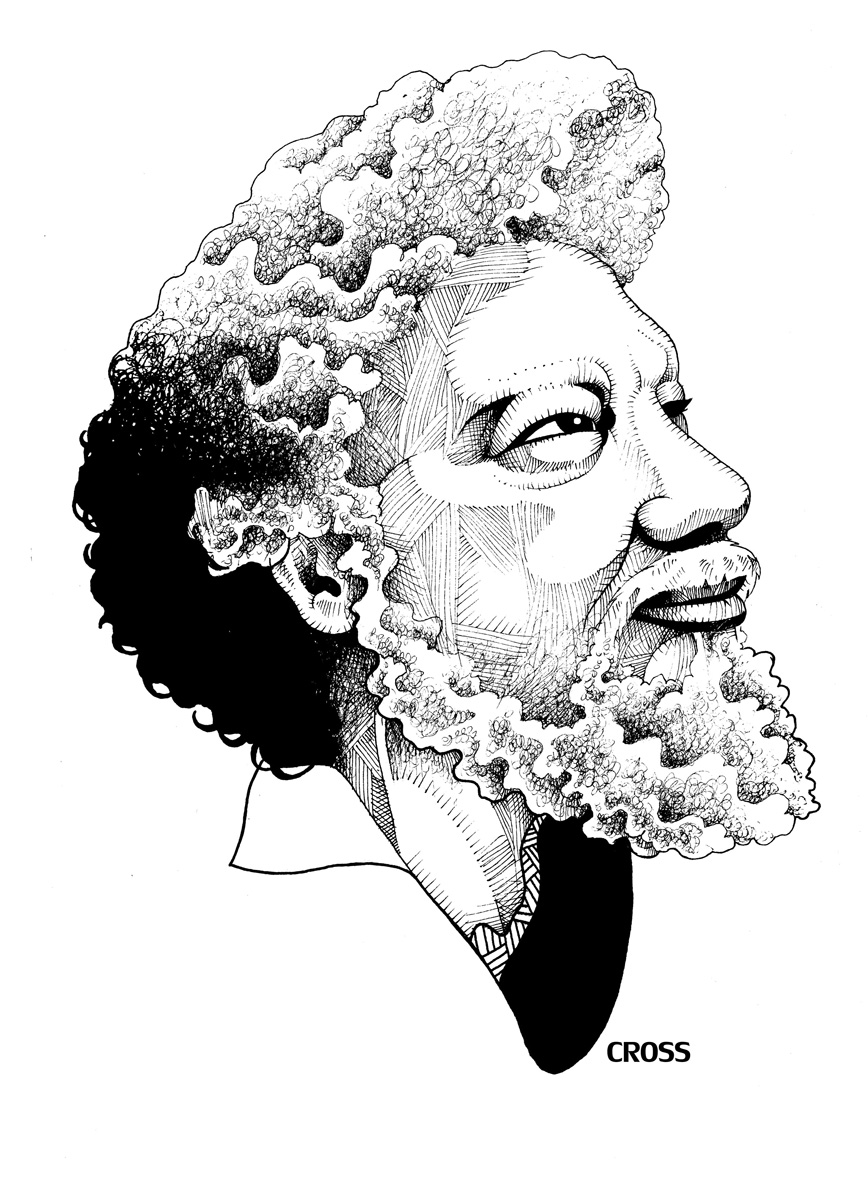

Romare Bearden (1911-1988)

Romare Bearden (1911-1988)

Poet, playwright, and political activist, Amiri Baraka, formerly known as LeRoi Jones, was one of the founders of the black arts movement. One of the prolific writers of his generation, Baraka received his BA in English from Howard University in 1954. After serving in the Air Force from 1954 to 1957, he went on to study at Columbia University and the New School of Social Research.

From 1957 to 1962, Baraka developed a critique of what he called acceptable “Negro art,” which he believed lacked the reflective quality of the black experience and pandered to the white middle-class. In response to the assassination of Malcolm X in February 1965, Baraka called for a black cultural revolution: one that used art as a weapon. By 1968, he and writer Larry Neal coedited the volume Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing, marking the beginning of the black arts movement.

Visual artist, educator, art critic, and social justice advocate, Benny Andrews was born into a sharecropping family in Morgan County, Georgia. After serving in the Air Force during the Korean War (1950–1953), Andrews used the G.I. Bill to attend the Art Institute of Chicago, where he honed his talents and eventually graduated in 1958. Moving to New York, he soon found himself at the center of the art world and was a major influence on his fellow artists’ attitudes toward social justice.

In 1969, Andrews co-founded the Black Emergency Culture Coalition (BECC), which led protest against the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Harlem on my Mind exhibition. The BECC argued that African Americans had been excluded from the planning process and that the show was more of an anthropological examination of black life than a substantive representation of black culture. The efforts of the BECC membership led to changes in the museums and galleries of New York, which had a ripple effect across the country. Black artists such as Camille Billops, Bing Davis, Joe Overstreet, and Faith Ringgold gained increased opportunities to show their work in venues more receptive to their aesthetic choices.

Poet, writer, novelist, activist, and teacher, Gwendolyn Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas, and grew up on the Southside of Chicago. After publishing her first poem at the age of 13, Brooks began attending workshops to hone her craft. Encouraged by her parents, Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes, and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson, she developed a voice and a style that reflected the beauty, as well as the ugliness, of urban Chicago.

In 1950, Brooks achieved acclaim after winning the Pulitzer Prize for poetry for her book Annie Allen, becoming the first African American to win the award. By the 1960s, at the beginning of the black arts movement, Brooks emerged as a critical supporter of a new socially, culturally, and politically conscious blackness—a new awareness that would shape the future of black people globally. In 1966, Brooks began publishing with Dudley Randall’s Broadside Press, a black-owned and -operated publishing house that supported the work of black authors.

Essayist, novelist, playwright, and civil rights activist, James Baldwin is best known for his provocative prose, which attacked the core of America’s hatred for the so-called “Negro.” At the age of 24, the Harlem native left the United States for France, where he would spend a majority of his life as an expatriate. Baldwin, whose muse was the exploration of the brutality of white American racism and the resulting black pathology, was a black gay man who sought freedom from the embedded system of oppression that fostered hatred and brutality toward black people.

In 1963, he published The Fire Next Time, an examination of the American enterprise and the challenges associated with being born in a country unwilling to see the humanity of its black citizens. This powerful indictment of white America resonated with African Americans, who celebrated his courage. By the summer of 1963, a reinvigorated and enthused Baldwin returned to the United States to participate in the March on Washington. He became one of the leading voices of the civil rights movement.

Poet, activist, playwright, and scholar, Sonia Sanchez is one of the most recognizable figures of the black arts movement. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, she moved to Harlem, New York, in 1943. She attended Hunter College, where she earned a degree in English in 1955. Sanchez continued her education at New York University, where she studied poetry and became active in the civil rights movement and a member of the Congress of Racial Equality.

By 1965, Sanchez—like many of her contemporaries—recognized that the fight for black liberation had to incorporate a major cultural shift in how black people thought about and saw themselves. Part of the evolving black arts movement, she interacted with Amiri Baraka and Larry Neal, and formed the “Broadside Quartet” with Don L. Lee (Haki Madhubuti), Nikki Giovanni, and Etheridge Knight. The radical group of young poets pushed for black nationalism and an Afrocentric framework to bring pride and dignity to black communities. In 1967, Sanchez helped establish the first black studies program in the country at San Francisco State University.

Writer, playwright, cultural critic, and visionary, Larry Neal was one of the central architects for the black arts movement. Born in Atlanta and raised in Philadelphia, Neal attended Lincoln University, where he studied English and history. In 1963, he took a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in English with an emphasis on folklore.

As a contributing writer, editor, and critic to the black nationalist publication The Liberator, Neal began to voice his ideas related to the development of a black aesthetic to direct the black power movement toward a more impactful cultural revolution. In 1968, Neal—along with Amiri Baraka—coedited Black Fire: An Anthology of Black Writing. The manifesto defined the realm of black art as a universe of social, cultural, and political importance that should serve to connect the artist with his or her primary audience in need of “new history, new symbols, myths, and legends.”

Poet, writer, documentary filmmaker, and producer, Mari Evans helped define the role of African American women’s literature in mid-century America. Born and educated in Toledo, Ohio, the talented Evans became a force in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as a member of the black arts movement. During that time, she received several awards, including the John Jay Whitney Foundation honorary award and a Woodrow Wilson Foundation grant.

In 1969, after taking a post at Indiana University in the English Department as a writer-in-residence, Evans published her first collection of poetry titled Where Is All the Music. A year later, I Am a Black Woman—a collection of poems speaking to the power of language and in support of strong black womanhood— was received with much acclaim. Evans’s poetry as well as her prose reflected the burgeoning black consciousness and aesthetic practices African American artists sought in an effort to be truly free.

Artist, author, and civil rights activist, Romare Bearden is one of the more recognizable and celebrated African American visual artists of the 20th century. His artistic production is spread over several forms of media, including oil, watercolor, photography, and collage. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, Bearden attended college at New York University, completing his BA in 1935. Traveling to Paris in 1950, Bearden studied art history and philosophy at the Sorbonne, developing some of the foundational techniques he would utilize throughout his illustrious career.

He was also active as an arts advocate for the African American community. In 1963, he formed the Spiral Group with fellow African American artists Norman Lewis, Reginald Gammon, Hale Woodruff, and Emma Amos, and others, to address issues related to race and racism, and the responsibility of black artists in support of the civil rights movement. By 1968, Bearden became the first director of the Harlem Cultural Council and helped to cofound the Studio Museum of Harlem and the Cinque Gallery to support the work of African American artists.